Transcatheter Ablation

Trans-catheter radiofrequency ablation of dual-way tachycardia

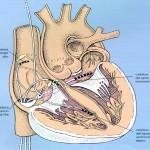

The atrioventricular node is formed by coalescence of two bundles of atrial fibers. These two beams not only have different electrophysiological properties, but appear to be two distinct anatomical structures; the anterior tract corresponds to the rapid route while the posterior tract corresponds to the slow route. To better visualize these two ways, it is very important to know the anatomy of Koch’s triangle. The three sides of the triangle are delimited by the tricuspidal annulus (the portion of the annulus adjacent to the septal cusp), the Todaro tendon and the ostium of the coronary sinus. The His bundle is located at the apex of the triangle. It is important to know that the apex of the Koch triangle (where the AV node and the His bundle are located) is an anterior structure, while the coronary sinus is posterior and defines the posterior portion of the atrial septum. In patients with TRN the slow and rapid pathway can be imagined as two bundles of atrial fibers: the rapid pathway is anterior and superior and is located along the Todaro tendon; the slow path is posterior and inferior and is localized along the tricuspid annulus near the ostium of the coronary sinus. Since these two routes are clearly identifiable, they can be subjected to the ablation procedure. Initially, the target for ablation was the rapid pathway, but, this being an anterior structure and very close to the AV node and the His bundle, about 20% of cases are complicated with a complete AV block. The target then moved to the slow path, which, being posterior and farther away from sensitive structures, shows a greater safety margin (the complete AV block in this case is described in less than 1% of cases). For the ablation of the slow path, two different approaches are possible: by electrophysiological or anatomical mapping. In both cases, the anatomical limits of the Koch triangle are first identified by placing a catheter on the His and one in the coronary sinus. The ablator catheter is then advanced through the femoral vein up to the tricuspid annulus near the CS ostium. In the case in which the slow route is to be mapped, the ablation catheter is carefully moved along the tricuspid annulus in search of the slow path potential, which represents its depolarization. In endocavitary ECG the slow path potential is localized between atrial deflection and ventricular deflection. When the slow path potential is identified, RF is delivered near this site. In the case of an anatomical approach, only fluoroscopic landmarks are used. Generally, the portion of tricuspid annulus between the ostium of the coronary sinus and the bundle of His is divided into three segments: posterior (near the coronary sinus ostium); medium; front (near the bundle of His). The catheter is positioned along the tricuspid valve and slid until the atrial and ventricular potential are recorded, with the atrial deflection larger than the ventricular deflection. At this point, radiofrequencies are delivered, and, generally, if the catheter position is correct, it is possible to observe junctional beats or junctional tachycardia. If after 10 or 15 seconds of RF there are no junctional beats, it is a good idea to stop dispensing and change the position of the scaler catheter. If, on the contrary, junctional beats appear, it is advisable to supply RF for another 30-60 sec. The success of ablation is documented by the impossibility of inducing arrhythmia during the electrophysiological control study.

The heart contracts thanks to specialized cellular structures that generate electrical impulses and regulate their distribution in the heart itself. Under normal conditions, the electrical impulse originates in the atrial sinus node, propagates in the atria and reaches the atrioventricular node, which is the only way of electrical communication between atria and ventricles; from here the impulse passes to the His bundle and to the intraventricular conduction system.

Related articles:

Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia Caused by 1:2 Atrioventricular Conduction in the Presence Of Dual Atrioventricular Nodal Pathways

Aureliano Fraticelli, Gabriele Saccomanno, Carlo Pappone and Giuseppe OretoJournal of Electrocardiology Vol. 32 No. 4 1999

Che cos’è un’ablazione transcatetere (ATC)?

L’ablazione transcatetere (ATC) è una procedura che consente di curare molte aritmie e consiste nell’eliminazione dei focolai o delle vie elettriche anomale che sono responsabili dell’aritmia stessa.

Come avviene l’ablazione transcatere?

L’ablazione viene eseguita solo dopo un esame del sistema elettrico del cuore (detto studio elettrofisiologico – SEE) e nella maggior parte dei casi si effettua nella stessa seduta.

Si introduce nelle camere cardiache un sondino di plastica con una punta metallica; di solito si utilizzano gli stessi vasi già usati per lo studio elettrofisiologico endocavitario. Nel caso l’aritmia abbia origine nel cuore sinistro è necessario introdurre il sondino anche nell’arteria femorale. Attraverso questo particolare catetere viene fatta passare energia elettrica, chiamata radiofrequenza (RF), che riscalda la punta metallica del catetere e può produrre piccolissime bruciature.

Si introduce nelle camere cardiache un sondino di plastica con una punta metallica; di solito si utilizzano gli stessi vasi già usati per lo studio elettrofisiologico endocavitario. Nel caso l’aritmia abbia origine nel cuore sinistro è necessario introdurre il sondino anche nell’arteria femorale. Attraverso questo particolare catetere viene fatta passare energia elettrica, chiamata radiofrequenza (RF), che riscalda la punta metallica del catetere e può produrre piccolissime bruciature.

Il catetere viene guidato dai raggi x e viene posizionato nella zona dove origina la aritmia o dove è più facile interrompere il circuito elettrico responsabile dell’aritmia: queste zone sono individuate attraverso dei segnali elettrici registrati dalla punta del catetere stesso. In questo modo la radiofrequenza viene applicata solo sul substrato della aritmia eliminandolo senza creare danni ai tessuti normali.

Il catetere viene guidato dai raggi x e viene posizionato nella zona dove origina la aritmia o dove è più facile interrompere il circuito elettrico responsabile dell’aritmia: queste zone sono individuate attraverso dei segnali elettrici registrati dalla punta del catetere stesso. In questo modo la radiofrequenza viene applicata solo sul substrato della aritmia eliminandolo senza creare danni ai tessuti normali.

La procedura viene normalmente effettuata in anestesia locale. Il paziente può quindi comunicare la presenza di qualsiasi disturbo al medico che sta effettuando l’esame. E’ però importante che il paziente rimanga fermo per impedire che il catetere si sposti dalla sua posizione, compromettendo il buon esito della procedura. Al termine dell’ablazione viene ripetuto lo studio elettrofisiologico e vengono rimossi tutti i gli elettrocateteri. La durata media della procedura di ablazione, a secondo della complessità dei casi, è di circa di 45-90 minuti.