Brugada Syndrome (BrS)

Indice dell'articolo

WHAT IS BRUGADA SYNDROME?

Brugada syndrome (BrS) is a genetic heart disease that carries an increased risk of sudden death.

The disease typically occurs during adulthood, on average around 40 years of age, and is estimated to be responsible for at least 4% of all sudden deaths, among which at least 20% of the deaths are of patients with a structurally normal heart.

Most diagnoses of BrS occur in young adults, often male, following the sudden death of a family member or with the occurrence of symptoms, such as syncope or cardiac arrest. The BrS has a characteristic electrocardiographic framework, represented by a typical over-leveling of the ST segment in the right precordial electrocardiographic leads (from V1 to V3), called Brugada pattern type 1. In cases where the electrocardiographic panel is suspected, but not diagnostic (Brugada pattern type 2 or 3), to confirm or exclude the diagnosis it may be necessary to carry out a test with class I antiarrhythmic drugs (e.g. ajmaline or flecainide), which unmask the diagnostic (type 1) Brugada pattern.

BrS patients generally have a structurally normal heart, although magnetic resonance imaging showed mild structural abnormalities of the right ventricle in a subset of patients.

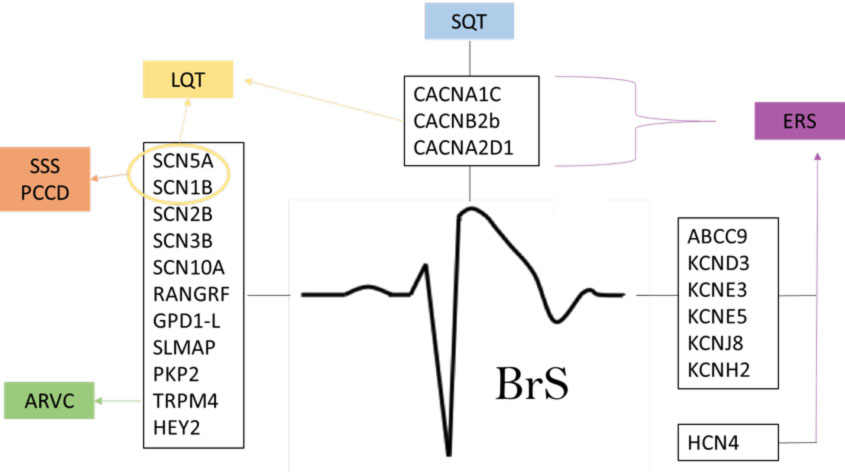

This disease seems to be linked to a malfunction of one or more ion channels, which are structures that allow the transit of these ions (sodium, potassium, magnesium and calcium) through the cell surface. The first genetic alteration identified in BrS was that of the SCN5A gene that codes for the sodium channel. Subsequently, numerous and further genetic anomalies have been associated with BrS, with more than 300 mutations described.

WHAT IS THE PREVALENCE OF BRUGADA SYNDROME?

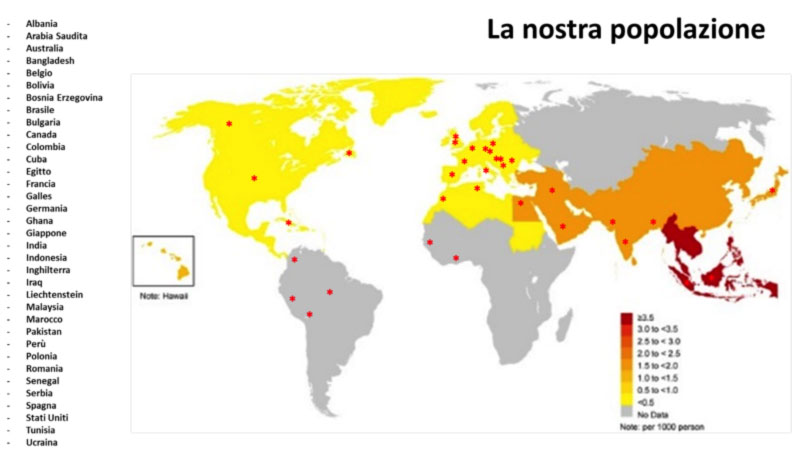

Since its first description, BrS has been of great interest, both for its high incidence in some parts of the world and because it is associated with an increased risk of sudden cardiac death, particularly in males in the third and fourth decade of life.

In fact, over the past few years, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of reported cases and scientific publications on the subject. A first Consensus Conference held in 2002 defined the diagnostic criteria for the syndrome. A second Consensus Conference in 2005 focused on risk stratification and therapies.

The prevalence of Brugada syndrome in the general population is estimated to be around 5:10,000 individuals (or approximately 0.05%). The disease is presumably widespread worldwide, with a similar incidence in Europe and the United States, tending to be even higher in Asian countries (Figure 1). The frequency is lower in western countries and higher in Southeast Asia, especially in Thailand and the Philippines, where Brugada syndrome is considered to be the main cause of sudden death in young individuals. In these countries, the syndrome is often referred to as SUNDS (sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome).

The disease is probably the leading cause of death in patients under 40 years of age. In any case, the pathology seems to be underestimated, due to the difficulties of diagnosis, due to the fact that the first symptom is often sudden death, and that the characteristic electrocardiographic pattern is highly variable over time.

AT WHAT AGE DOES BRUGADA SYNDOME NORMALLY AFFECT PEOPLE?

Brugada syndrome typically occurs in youth and adulthood, generally after adolescence, with an average age at the presentation of symptoms of around 40 years (41 ± 15 years in our case history). Typically men show the disease more frequently than women (with a ratio of about 5:1 in our case history). More rarely, BrS occurs in children, and could explain some cases of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

WHAT ARE THE GENETIC CHARACTERISTICS OF BRUGADA SYNDROME?

BrS is a genetic disease with predominantly autosomal dominant transmission. Therefore, the probability of transmitting the pathology is 50% with each pregnancy. The genetic investigation, performed starting from a simple blood sample, is important not only for the clinical management of the patient, but above all for the identification of any other affected family members.

According to literature data, in patients in whom a gene mutation is discovered, in about 50% of cases a mutation is observed in the SCN5A gene, a gene involved in the function of the sodium channel, while the remaining cases have anomalies in other genes.

In the case of probands with a suspecision of BrS, in our center, genetic screening is carried out on a blood sample using the NSG (Next Generation Sequencing) method on a panel of 25 genes (ABCC9, AKAP9, CACNA1C, CACNA2D1, CACNB2, DSC, DSG2, GPD1L, HCN4, KCND2, KCND3, KCNE3, KCNE5, KCNH2, KCNJ8, MOG1, PKP2, RANGRF, SCN5A, SCN10A, SCN1B, SCN2B, SCN3B, SEMA3A, TRPM4).

If you want to know more >> Cardiogenetics.

| Brugada syndrome is one of the main focuses of our center’s clinical and research activity. To date, over 300 families with BrS have been studied in our center, for a total of more than 1000 individuals. |

WHY PERFORM FAMILY SCREENING IN CASE OF SUSPECTED BRUGADA SYNDROME?

Given the genetic origin of the syndrome, investigating family history is very important. BrS patients may have a positive family history of sudden death at a young age (i.e. less than 50 years of age) from unknown causes. Other aspects that deserve further study are the possible presence of family members diagnosed with epilepsy or a history of repeated abortions or unexplained infant deaths in the family.

In the event that, during family screening, affected family members are identified, there is the need to perform further investigations for the stratification of any arrhythmic risk.

WHAT ARE THE ELECTROCARDIOGRAPHIC SIGNS OF BRUGADA SYNDROME?

The electrocardiogram (ECG) of the affected patient can vary a lot over time, even within the same day, passing from moments in which the tracing is substantially normal to others in which it becomes frankly pathological.

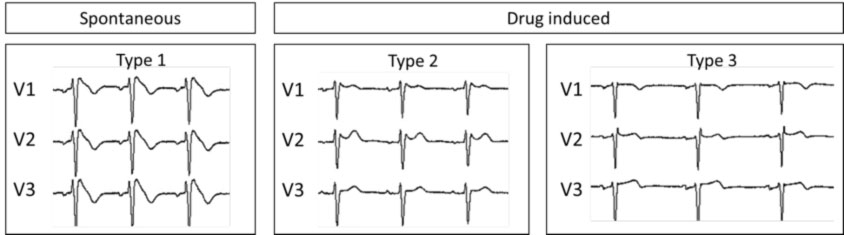

The disease can have three different ECG pictures (also called ECG “phenotypes”), of which only Type 1 is actually diagnostic for Brugada syndrome (Figure 2).

- Type 1 is the so-called “elevation of the ST coved type”, with an elevation of the J point of at least 2 mm (with “curtain” morphology) and a gradual descent of the ST segment and a negative T wave in V1 and V2.

- Type 2 has the so-called “saddle-back pattern” (“saddle aspect”), with an elevation of the J point of at least 2 mm and an elevation of the ST section of at least 1 mm with a positive or biphasic T wave.

Type 3 it has the so-called “saddle-back pattern” with an elevation of the J point of less than 2 mm, an elevation of the ST section of less than 1 mm and a positive T wave. Type 3 is very unspecific since it is also present in healthy subjects, in particular in athletes and in young subjects.

| In doubtful cases (spontaneous Brugada type 2 or 3 pattern), the execution of a provocative pharmacological test (Ajmaline) is recommended, to unmask the type 1 pattern and therefore diagnose BrS. |

The presence of anomalies in the peripheral or lateral branches (particularly aVR) has also recently been reported as an additional risk factor.

Other conduction disturbances have also been described in Brugada syndrome such as:

- atrioventricular block (AVB) (conduction delay has been reported to be sub-Hissian and that the H-V interval is prolonged in most patients);

- intraventricular conduction disorders (cases of isolated right bundle branch block or associated with left anterior hemiblock have been reported).

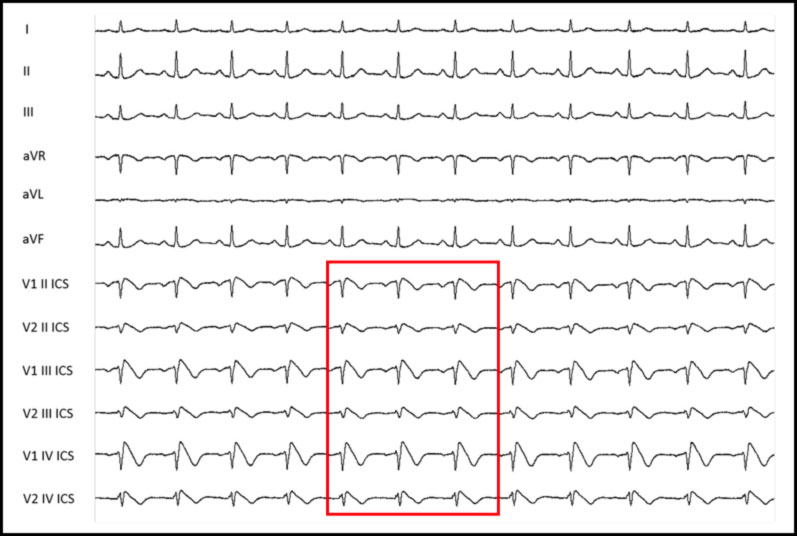

HOW SHOULD THE ELECTRODES BE POSITIONED TO HIGHLIGHT THE BRUGADA PATTERN IN THE ELECTROCARDIOGRAM?

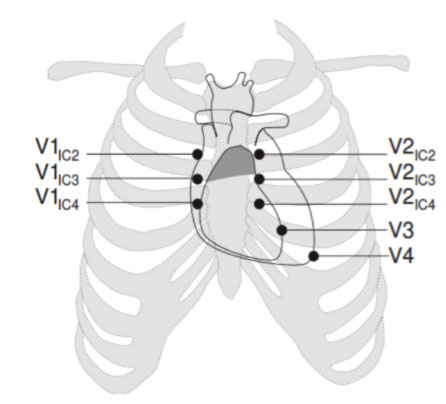

To identify the possible presence of spontaneous Type 1 patterns, it may be necessary to position the precordial leads in the 2nd and 3rd intercostal space instead of in the classic 4th intercostal space.

This allows to increase the possibility of identifying the typical electrocardiographic anomaly and therefore to diagnose BrS. This happens because the Brugada phenomenon, in basal conditions, occurs in a very limited portion of the right ventricular region, whose potentials are detected only if the electrodes are placed practically above the affected region.

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS OF BRUGADA SYNDROME?

Characteristic of the BrS is the extreme variability of the clinical presentation.

Unfortunately, in a considerable percentage of patients, the first clinical manifestation of the disease is sudden death, due to fatal ventricular arrhythmias. The latter catastrophic event underlines the difficulty of managing the disease in predicting which individuals will be at greatest risk, since before this event, the vast majority of patients do not present with any warning symptoms.

Affected patients may also be totally asymptomatic or exhibit symptoms due to cardiac arrhythmias, with episodes of syncope (i.e. loss of consciousness), episodes of palpitations or heart rate. Sometimes patients may have seizures and symptoms that can be confused with epilepsy. Symptoms often occur at rest, in the recovery phase from exercise or during night sleep.

HOW IS THE DIAGNOSIS OF BRUGADA SYNDROME CARRIED OUT?

A timely diagnosis is crucial for this syndrome, as the affected patient may be at risk of potentially fatal arrhythmias. When the suspicion of Brugada syndrome has been raised, family history and the electrocardiographic tracing must be obtained, and other cardiological tests performed, including echocardiogram (to exclude the presence of any heart disease).

Confirmation of a Brugada syndrome diagnosis is possible with the presence of a spontaneous type 1 pattern.

However, in most cases, the ECG pattern is suspicious of BrS, but not diagnostic (type 2 or 3 pattern), and it may be necessary to resort to a pharmacological test with Ajmaline, which in predisposed subjects induces the appearance of the Brugada pattern type 1, and therefore allows to exclude or confirm the diagnosis of Brugada syndrome.

In the case of a positive pharmacological test, an endocavitary electrophysiological study (EES) may be necessary, in order to verify the possible vulnerability of a patient to potentially malignant ventricular arrhythmias.

WHAT IS THE PHARMACOLOGICAL TEST FOR BRUGADA SYNDROME?

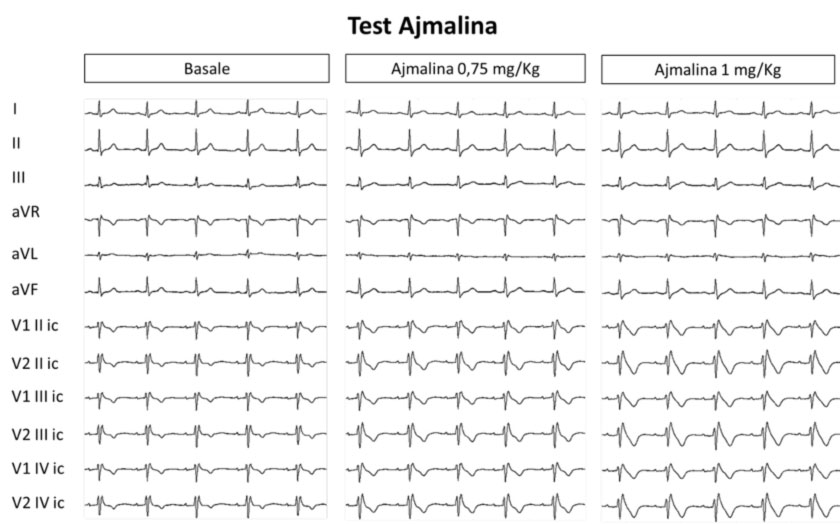

The provocative pharmacological test “Ajmaline test“, consists of the administration of a drug blocking the sodium channels (ajmaline), which unmasks the Brugada type 1 pattern in cases where the electrocardiographic anomalies are not already diagnostic for BrS.

In fact, this provocative test is useful in patients with ECG patterns type 2 and 3. In these cases, the test is positive (diagnostic) when the drug induces a transformation of the ECG pattern into type 1. In patients with spontaneous type 1 patterns, the test is not recommended.

The provocative pharmacological test is not intended to cause arrhythmias, but in particularly high-risk cases, ventricular arrhythmias may arise. Therefore, the provocative pharmacological test is carried out in a suitable environment and in the presence of personnel trained to deal with the onset of arrhythmias.

If you want to know more > provocative pharmacological tests

FOR WHAT IS THE ENDOCAVITARY ELECTROPHYSIOLOGICAL STUDY (EES)?

The endocavitary electrophysiological study (EES), through programmed ventricular stimulation, is used to verify the inducibility of ventricular arrhythmias, i.e. the predisposition of a certain patient to develop potentially fatal arrhythmias.

Since patients with Brugada syndrome are at risk of sudden death, EES is carried out in subjects suffering from the syndrome in order to be able to recognize patients at risk of spontaneously developing ventricular arrhythmias.

At present, the EES is, however, one of the few useful tests available for an adequate risk stratification in the individual patient, and is used to guide the choice of the most appropriate therapeutic strategy.

WHICH DRUGS ARE TO BE AVOIDED IN BRUGADA SYNDROME?

Many cardiac or non-cardiac drugs can provoke the appearance or amplify the Brugada type 1 pattern in affected individuals. The complete list of drugs to avoid can be downloaded here or at www.brugadadrugs.org.

In particular, patients should avoid the administration of antiarrhythmic drugs blocking the sodium channels (specifically Ajmaline and Flecainide or Propafenone, etc.), which can also be used as provocative pharmacological tests to confirm the diagnosis of the disease.

It should be noted that, in some patients, the diagnosis of Brugada syndrome is carried out occasionally following the administration of flecainide or propafenone for atrial arrhythmias, in particular for atrial fibrillation. Therefore, in general, it is always recommended to carry out a 12-lead ECG before and after starting therapy with class 1 antiarrhythmic drugs.

ARE DRUGS DANGEROUS FOR PEOPLE WITH BRUGADA SYNDROME?

| In patients with Brugada syndrome, it is important to avoid alcohol, smoking, and drug abuse (in particular cocaine), which can induce the onset of potentially fatal ventricular arrhythmias. |

WHAT ARE THE MOST FREQUENT ARRHYTHMIAS IN BRUGADA SYNDROME?

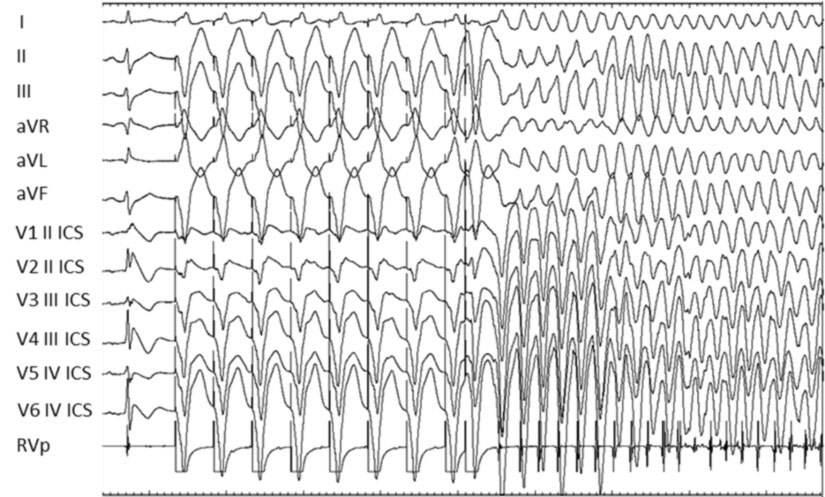

The sudden death linked to the onset of malignant ventricular arrhythmias can unfortunately represent the first clinical manifestation of Brugada syndrome. Among these arrhythmias, the most frequent is polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, which degenerates into ventricular fibrillation and therefore causes cardiac arrest. These ventricular arrhythmias can be triggered by ventricular ectopic beats, i.e. ventricular extrasystoles.

The wide spectrum of anomalies related to Brugada syndrome include, in a non-negligible percentage, bradyarrhythmias, such as sinus-atrial blocks and paroxysmal atrio-ventricular blocks, which can, in turn, increase the risk of sudden death.

In addition, BrS patients may also experience a range of other atrial arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation and paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardias (SVT), which can affect quality of life. These arrhythmias, although non-malignant, can represent warning signs of a genetic disease, especially if they occur at a young age in people without structural heart disease. Therefore, in specific cases, an accurate specialist assessment is necessary in order to exclude the possibility of BrS.

WHAT ARE THE TREATMENTS RECOMMENDED FOR BRUGADA SYNDROME?

Once the diagnosis of BrS is made, the therapeutic approach depends on the patient’s level of risk. Brugada syndrome does not present with a definite clinical progression, and therefore a patient may experience new clinical elements indicative of a possible change in the level of risk. Therefore, it is appropriate to carry out checks every six months.

Currently the therapeutic options available for Brugada syndrome are essentially of three types:

- Implantation of cardiac defibrillator (ICD, intracavitary or subcutaneous) or implantable cardiac monitors (subcutaneous ICM or loop recorder)

- Transcatheter epicardial ablation of the arrhythmic substrate

- Drug therapy with specific antiarrhythmic drugs (Quinidine)

In our center, we have developed an approach based on the clinical characteristics of each individual, born from our wide and long clinical experience with thousands of cases followed with a long follow-up.

WHEN TO USE THE CARDIAC DEFIBRILLATOR (ICD) AND CARDIAC MONITOR (ICM) SYSTEM IN BRUGADA SYNDROME?

ICD is the only therapy with proven efficacy in preventing sudden arrhythmic cardiac death.

The implantation of a defibrillator is necessary in the event of a finding of BrS that presents with high risk characteristics. The risk stratification is based on an evaluation of a series of objective clinical parameters (electrocardiographic, non-invasive, clinical parameters deriving from the electrophysiological study) together with the presence of symptoms attributable to potentially lethal arrhythmias.

Given the possible presence of supraventricular arrhythmias or disturbances of the condition, the use of the intracavitary defibrillator is generally preferred, even if in younger subjects, or in patients who have had problems related to the intracavitary defibrillator you can opt for the implantation of a subcutaneous defibrillator.

An approach that is based on multiple parameters is always necessary in order to optimize the most appropriate therapeutic choices, based on the clinical needs of each individual patient. In fact, each of these choices is based on the assessment of the risk of developing potentially fatal arrhythmias, and this is carried out both in the adult and pediatric population. In the latter context, in the most serious and most risky cases it is possible to implant a defibrillator. Instead, in conditions of apparently lower risk, it is possible to offer the implantation of a cardiac monitor under the skin (implantable cardiac monitor ICM or better known as loop recorder) that constantly records the electrocardiogram. The latter offers the possibility of monitoring patients for many years in order to document any arrhythmias that may change the assessment of the arrhythmic risk over time, and therefore modify the therapeutic strategy if indicated.

Each of these devices, ICD or ICM, are available in association with remote monitoring technology, better known as home monitoring. This technology allows you to monitor the operation of these devices remotely while the patient is at home. A modem connected wirelessly records the information of the implanted device and sends it to a secure website, which is only accessible to doctors. In this way, doctors can check not only the correct functioning of the device, but also the onset of any arrhythmias, so that they can intervene promptly with the most appropriate therapeutic strategies.

WHEN TO PERFORM EPICARDIAL ABLATION OF THE ARRHYTHMIC SUBSTRATE IN BRUGADA SYNDROME?

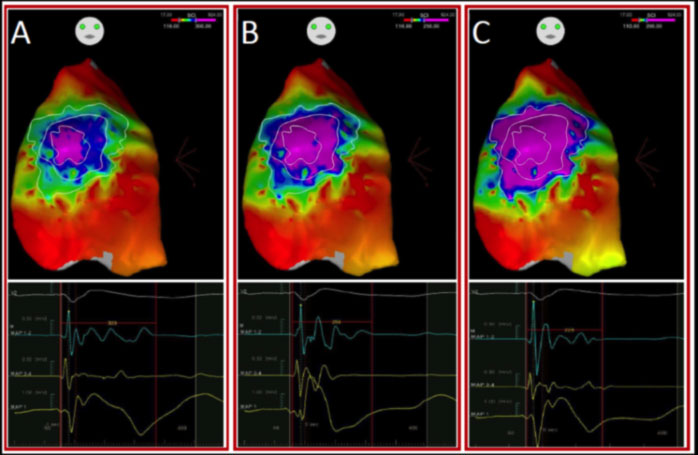

In 2015, our team led by Prof. Pappone demonstrated that the arrhythmogenic substrate of Brugada syndrome is preferentially located in the epicardial region of the outflow tract and the anterior wall of the right ventricle. These areas are characterized by the presence of abnormal electrical potentials that can give rise to those arrhythmias capable of triggering cardiac arrest in patients with BrS.

Once the epicardial arrhythmogenic substrate has been precisely identified, our team has always shown that epicardial ablation by radio frequency is able to eliminate all electrical anomalies, and this leads to the immediate disappearance of the electrocardiographic pattern of Brugada syndrome and the absence of ventricular arrhythmias in follow-up.

This procedure was proposed and developed in our center, which is the most experienced center in the world for this type of intervention.

Currently more than 600 patients with Brugada syndrome have undergone ablation, with an extremely low incidence of perioperative complications.

The ablation strategy proposed by our group can be applied safely and effectively to a greater number of patients with Brugada syndrome considered at risk.

This experience is the largest case history in the world of patients with BrS treated by ablation, and this establishes the first step for a new strategy for the treatment of BrS available to affected patients.

WHEN TO CARRY OUT PHARMACOLOGICAL THERAPY WITH QUINIDINE IN BRUGADA SYNDROME?

Drug therapy with quinidine, although effective in general terms, is burdened by numerous side effects that prevent its prolonged and continuous use. This means that this therapy cannot be in any way a substitute for the aforementioned therapies, and is therefore reserved only for those who continue to have arrhythmic recurrences. However, it has been widely demonstrated that the latter category of patients benefits better from ablative therapy compared to chronic drug therapy.

I HAVE BRUGADA SYNDROME. ARE THERE ANY SPECIAL PRECAUTIONS I NEED TO TAKE IF I HAVE A COVID-19 INFECTION?

The link between hyperpyrexia (fever) and the onset of a type 1 Brugada syndrome pattern and cardiac arrhythmias has been known for years. Therefore, patients with Brugada syndrome (both with spontaneous and drug-inducible type 1 patterns) are particularly at risk of fatal arrhythmias if their body temperature exceeds 37.5° C. These patients must therefore treat fever aggressively with the use of paracetamol and warm / cold sponging.

The increase in body temperature could, in fact, alter the function of the cardiac ion channels, leading to potentially fatal arrhythmias.

In the case of COVID-19 infection, other factors besides fever could favor the genesis of cardiac arrhythmias, including stress, the use of potentially pro-arrhythmic drugs, and imbalances of blood electrolytes.

Therefore, in patients suffering from Brugada Syndrome with particularly high temperatures (above 38.5° C despite therapy with antipyretic drugs such as tachipirina), hospitalization and, in some cases, intensive care, is warranted to monitor the ECG.

I HAVE BRUGADA SYNDROME. CAN I GET VACCINATED AGAINST COVID-19 AND ARE THERE ANY SPECIAL PRECAUTIONS I NEED TO TAKE IF I AM VACCINATED AGAINST COVID-19?

There is no specific data concerning the use of the COVID-19 vaccine in patients with Brugada syndrome. Given the risks associated with COVID-19 infection, particularly in patients at risk of cardiac arrhythmias, we generally recommend patients with Brugada syndrome, even in young people, to undergo prophylactic vaccination.

As for the type of vaccine, given that many of the affected patients are young, it is still preferable to use anti m-RNA vaccines. In any case, we recommend the use of antipyretic drugs in the event of a post-vaccination rise in body temperature (with tachipirina in case of fever greater than 37.5° C).

In the case of Brugada syndrome patients with specific comorbidities (for example oncological, neurological, autoimmune or hematological, acute or chronic diseases), the decision to carry out the COVID-19 vaccination must be made on a case-by-case basis, after a careful individual evaluation of the risk-benefit ratio.