Ventricular Extrasystoles (PVC)

Indice dell'articolo

What are ventricular extrasystoles?

Ventricular premature (or extrasystolic) beats (also called BEV, or PVC, premature ventricular contraction) are single ventricular impulses due to an abnormal automation of the ventricular cells or the presence of re-entry circuits in the ventricle. Ventricular extrasystoles are isolated beats common in clinical practice, and can be symptomatic (giving palpitations as a symptom) or asymptomatic. In this case, the finding of arrhythmia is usually random, mostly during screening visits. In most cases these arrhythmias are benign and do not require any intervention. In some cases they can be a signal of a cardiac pathology, sometimes potentially threatening, or they can be associated (and in some cases cause) a dysfunction of the contraction of the left ventricle.

What is the prevalence of ventricular extrasystoles?

The prevalence of isolated ventricular extrasystoles generally increases with age and with the presence of heart diseases. In normal subjects, isolated ventricular extrasystoles are found in about 1% of subjects subjected to standard ECG. Among healthy subjects undergoing dynamic ECG recording for 24-48h, extrasystoles can be quite frequent (> 60 PVC per hour), often monomorphic (i.e. of a single morphology), more rarely polymorphic (in 5% of cases) (of multiple morphologies). Extrasystoles are more frequent in patients with cardiac disease, especially ischemic heart disease, previous myocardial infarction, heart failure, hypertensive cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, dilated cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, and noncompaction cardiomyopathy.

What is the prognosis for isolated ventricular extrasystoles?

The prognosis of isolated ventricular extrasystoles essentially depends on the presence of structural heart disease or any channelopathy. Various studies in the literature confirm the benign nature of isolated ventricular extrasystoles, even frequent, in the healthy heart. However, some studies (e.g. the Framingham study) had found that ventricular extrasystoles were associated with an increased risk of cardiac death, myocardial infarction and death from all causes, but the conclusions of these two studies were, however, criticized for the absence of investigations aimed at excluding the presence of structural cardiac pathologies and, in particular, of hypertensive heart disease. In fact, several studies have shown that there is an evident correlation between ventricular extrasystole and prevalence of hypertensive heart disease, which explains the increase in mortality regardless of the presence of arrhythmias.

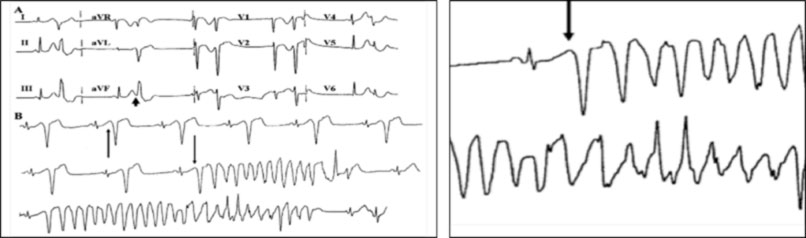

The prognosis of the ventricular extrasystoles is also a function of their electrocardiographic characteristics, in particular the number, the shorter coupling interval (with the “R on T” phenomenon), the presence of Holter recordings also of frequent non-sustained high ventricular tachycardias, and from the response to exercise (stress test) or in some cases to the electrophysiological study. The appearance of ventricular extrasystoles during or immediately after exercise identifies a group of subjects at higher risk of developing malignant ventricular arrhythmias, associated or not with structural heart disease.

In the case of patients with a cardiac pathology, the prognosis varies according to the type and severity of any heart disease. Therefore, in the case of frequent ventricular extrasystole, the presence of underlying congenital or acquired cardiac disease, structural or primarily electrical, should always be excluded. In the absence of structural heart disease, the presence of channelopathies should therefore be excluded, in particular the presence of the Brugada pattern (suggestive of Brugada syndrome) and the prolongation of the QT interval (suggestive of long QT syndrome).

In the case of frequent ventricular extrasystolia from the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT), which probably represents the most frequent form of ventricular extrasystolia, in the absence of structural cardiac anomalies, the prognosis is generally good, although the presence of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) must be very carefully excluded. In this case, in addition to BEVs with the typical vertical axis left bundle branch block (LBBB) morphology, other ECG anomalies are often present, such as right conduction delay and ventricular repolarization anomalies in the anterior precordial leads.

Finally, frequent ventricular extrasystole can contribute to the development of heart failure, both in patients with left ventricular dysfunction, but also in subjects with a structurally normal heart. In particular, patients with frequent ventricular extrasystole (> 20% of total beats) even in the absence of known structural heart disease, may present with progressive left ventricular dysfunction and a prevalence of insufficiency. The correlation between frequent ventricular extrasystole and the development of left ventricular dysfunction is then confirmed by the evident improvement of the contractile function of the left ventricle in subjects subjected to effective ablation. Therefore, in subjects with a structurally normal heart but with very frequent ectopias, it is necessary to monitor the function of the left ventricle and evaluate the possible indication to proceed with transcatheter ablation.

Is it possible to do sports in case of ventricular extrasystole?

The finding of ventricular extrasystole found during a sports-medical visit has practical implications, in particular linked to the granting of fitness for competitive sports. Ventricular extrasystoles are frequently found in athletes, with a dynamic ECG prevalence of about 2%, generally with a benign prognosis. Generally there is the disappearance or reduction of arrhythmias after detraining, suggesting that the ventricular extrasystoles in the sportsman have a causal link with training and therefore can be interpreted as an expression of an athlete’s heart. Therefore, in the case of frequent ventricular extrasystole in sports subjects, screening for cardiac disease should be performed, and detraining may be recommended to assess the time course of arrhythmias.

What diagnostic tests should be performed in case of ventricular extrasystole?

In case of ventricular extrasystole, a complete evaluation is necessary which includes family history (to exclude history of syncopes or sudden death), personal history (to evaluate the history of palpitations or syncopes, and exclude the presence of non-cardiac diseases, including anemia or thyroid disorders, or the use of stimulants or drugs), and the acquisition of the 12-lead ECG (to exclude signs of previous necrosis and abnormalities of intraventricular conduction and repolarization).

The diagnosis of ventricular extrasystole is based on the execution of dynamic ECG according to Holter, initially for 24 hours, and possibly more prolonged to assess any variability in the following days. ECG Holter enables the evaluation of the number of extrasystoles, the presence of any repetitive forms (unsupported ventricular tachycardias), the presence of any R-on-T phenomena, and the circadian trend of extrasystoles. These characteristics have diagnostic and prognostic significance. For example, a high nocturnal incidence of extrasystoles could suggest the concomitant presence of sleep apnea syndrome. The ECG Holter is generally repeated over time to evaluate the complexity and variability of arrhythmias, and the possible appearance of unsupported ventricular tachycardias.

Other tests that are performed are the stress test (or ergometric test) to evaluate the behavior of the ventricular extrasystoles with effort, given that the disappearance of arrhythmias during effort (called “overdrive suppression”) is considered a sign that it is benign, conversely, an increase in the frequency or complexity of extrasystoles with exercise is considered a negative prognostic sign, indicative of underlying heart disease (e.g. ischemic, or hypertensive heart disease, arrhythmogenic heart disease, including possible catecholaminergic ventricular tachycardia).

The other fundamental examination is echocardiography, to exclude an organic heart disease and evaluate myocardial and valve function. In some cases, it is then indicated to carry out second level tests, such as cardiac magnetic resonance imaging or possibly coronary angiography or coronary angiography.

What is the therapy for ventricular extrasystoles?

In the case of even frequent ventricular extrasystole, very often it is sufficient to reassure the patient, making him certain of the benignity of his condition and informing him of the variability of arrhythmias, which can reduce and even disappear over time. Among non-pharmacological therapies, the reduction of the consumption of exciting substances, in particular of caffeine, smoking, the consumption of alcohol or any narcotic drugs (in particular cocaine) is fundamental.

Therefore, non-cardiac favorable conditions (such as anemia and thyroid diseases) must be corrected. Adequate blood pressure control is also important, which is one of the most common causes of frequent ventricular extrasystole. A careful analysis of the ECG and a correct clinical-instrumental evaluation are therefore fundamental to identify the subjects who need therapeutic intervention.

In the case of ventricular extrasystole in a healthy heart, antiarrhythmic therapy is not generally necessary, which should be reserved for particular cases, for example in cases of very disturbing symptoms. Generally the first choice drugs are beta-blocker drugs (bisoprolol, sotalol or nadolol), which show a fair effectiveness especially in patients who have a mainly diurnal extrasystole, a phenomenon suggestive of an adrenergic hyperactivity. Other potentially effective antiarrhythmic drugs are flecainide, propafenone and amiodarone, but their chronic use is not recommended because of possible side effects, including the possibility of being proarrhythmic.

Transcatheter ablation is therefore to be considered in patients in the absence of structural heart disease with very frequent ectopias, particularly when the echocardiogram demonstrates a trend towards reduced ventricular function.

In summary, isolated ventricular extrasystoles are commonly observed in clinical practice, both in symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects. In the latter, the finding of arrhythmia is often random, mostly on the occasion of screening visits. In most cases these arrhythmias are benign and do not require any intervention. In some cases they are instead the signal of an arrhythmogenic cardiac pathology, sometimes potentially threatening, or they can lead to contractile dysfunction of the left ventricle, and must therefore be studied and possibly treated.

If you need a visit or diagnostic test for ventricular extrasystole, click here