Atrial Fibrillation (AF)

Indice dell'articolo

What is atrial fibrillation?

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a very frequent arrhythmia, as it affects 1-2% of the population, and the chances of developing this condition increase with advancing age.

Under normal conditions, the heart contracts thanks to specialized cellular structures that generate electrical impulses and regulate their distribution in the heart itself. The electrical impulse originates in the atrial sinus node, located in the right atrium, propagates in the atria and reaches the atrio-ventricular node, which is the only way of electrical communication between the atria and ventricles; from here the impulse passes to the His bundle and to the intraventricular conduction system.

There is talk of atrial fibrillation when the electrical activation of the atria derives from the continuous and chaotic circulation of the impulse along the atrial walls: the atria no longer contract in a coordinated manner, but have a chaotic activity, called “fibrillation”.

How is atrial fibrillation defined?

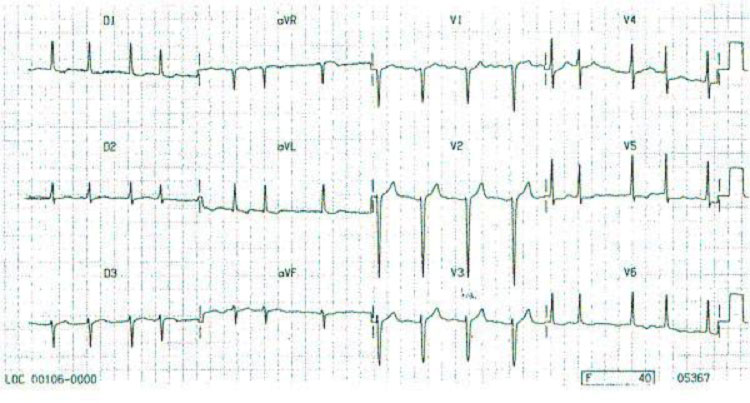

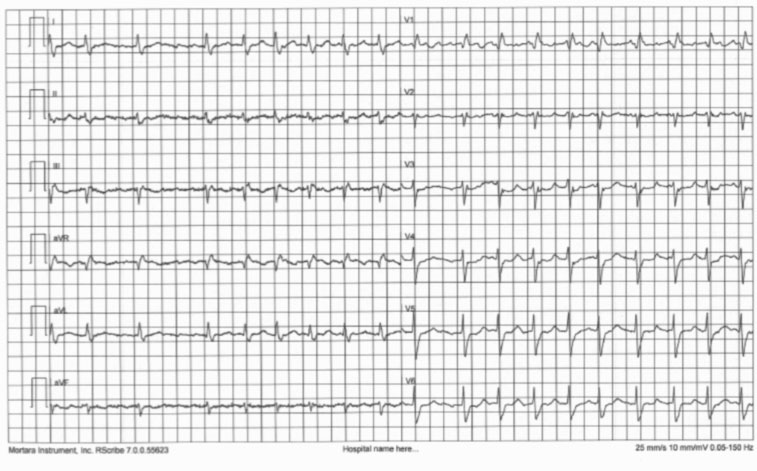

Atrial fibrillation is a supraventricular arrhythmia, the electrocardiographic diagnosis of which is based on the following two elements:

- absence of P waves

- irregularities of R-R intervals

In atrial fibrillation, the activation of the atria is chaotic and continuously variable, so the P waves disappear and are replaced by small waves called f waves. The f waves are completely irregular, have continuous changes in morphology, voltage and intervals ff, have very high frequency (400-600 rpm) and last throughout the cardiac cycle (they are continuous) resulting in a jagged appearance of the isoelectric line (particularly visible in branches V1-V2).

In atrial fibrillation, a large number of atrial impulses reach the atrioventricular (AV) junction, but only a part of these then reaches the ventricle. The AV node performs a filter function: numerous impulses only partially penetrate the node and are blocked within it. This irregularity of AV conduction causes the R-R intervals to be variable. The number of atrial impulses that are conducted to the ventricles is defined as a ventricular response, which can be high (or tachycardia, when the number of impulses is greater than 100 impulses per minute) or low (bradycardia, when the number of impulses is less than 50 pulses per minute).

The continuous variation of ventricular cycles constitutes the cardinal element in the diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, so much so that when the arrhythmia occurs with constant R-R intervals, it is less unlikely that it is atrial fibrillation, but more likely that it is a supraventricular tachycardia.

What are the types of atrial fibrillation?

There are three different types of atrial fibrillation, essentially defined by duration:

- Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: form characterized by spontaneous interruption of arrhythmia, generally within 7 days, mostly within 24-48 hours;

- Persistent atrial fibrillation: arrhythmia (regardless of its duration) does not stop spontaneously but only with therapeutic interventions (pharmacological or electrical cardioversion);

- Permanent or chronic atrial fibrillation: form in which no attempts to stop the arrhythmia have been made or, if they have been made, have not been successful due to failure to restore the sinus rhythm, or for immediate recurrence, or in which further attempts at cardioversion are not indicated.

What is the prevalence of atrial fibrillation?

The prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the general population is reported to be around 1%, depending on the different studies. The prevalence appears relatively low in young subjects and progressively increases with advancing age. In the North American ATRIA study, the prevalence in the general population is 0.9%, but it is 0.1% in subjects < 55 years of age and 9% in subjects > 80 years of age. In the Framingham study, the prevalence is 0.5% in the 50-59 age group, 1.8% in the 60-69 age group, 4.8% in the 70-79 age group, and 8.8% in the 80-89 age group. About 70% of patients with atrial fibrillation are over 65 years old with a median age of 75 years. The prevalence appears slightly higher in men than in women in all age groups (1.1% versus 0.8%, in the ATRIA study).

According to data from the Istituto Superiore di Sanità, atrial fibrillation is currently the most frequently sustained arrhythmia in clinical practice in Italy, with a prevalence in the general population of 0.5-1%. It is possible to estimate that the number of patients suffering from atrial fibrillation in Italy are around 610,000 people (10% of the total population). The prevalence has gradually increased over time and is expected to further increase in the coming years, given the rapid aging of the population and the growing number of subjects over the age of 65.

What conditions predispose a person to atrial fibrillation?

As far as the etiopathogenesis, atrial fibrillation can be primary or secondary.

Primary, idiopathic, or isolated atrial fibrillation is not associated with organic heart disease or other clinical situations related to arrhythmia (bronchopneumopathy, hyperthyroidism, etc.). The prevalence of primary atrial fibrillation is variable (around 5%).

Secondary atrial fibrillation, on the other hand, is one in which a cause of arrhythmia or a condition that causes arrhythmia can be identified. Among the factors that predispose to atrial fibrillation, the main conditions are the following:

- hypertension

- heart valve diseases, especially mitral and aortic valves

- coronary heart disease

- congestive heart failure

- genetic arrhythmogenic heart diseases and channelopathies

- congenital heart disease

- pericarditis

- hyperthyroidism

- diabetes mellitus

- anemia

- gastrointestinal disorders (gastric ulcer, cholelithiasis)

- chronic obstructive bronchopathy (COPD)

- kidney failure

- sleep apnea

- tobacco smoke

- alcohol consumption

- intense physical activity

What are the symptoms of atrial fibrillation?

The symptoms of atrial fibrillation are extremely variable from patient to patient, and can be from very marked to almost absent.

The most frequent symptoms, in decreasing order according to the ALFA study, are palpitations (54.1%), dyspnea (44.4%), fatigue (14.3%), syncope (10.4%) and chest pain (10.1%). Palpitations prevail in the paroxysmal form (79%), while dyspnea in the chronic and recent onset (46.8% and 58%, respectively).

In addition to symptomatic, atrial fibrillation can also be asymptomatic or silent, representing an occasional finding on standard ECG or dynamic ECG Holter in about 20% of cases.

What is silent atrial fibrillation?

Many patients, especially elderly patients, or patients with other pathologies and in multitherapy, can be completely asymptomatic, and in this case we speak of silent AF. In these patients, the detection of AF often occurs entirely occasionally, or in conjunction with hospitalization for an episode of heart failure, caused precisely by an unrecognized rapid atrial fibrillation. Silent atrial fibrillation is no less dangerous for this, but it is more difficult to diagnose, and more insidious, because even if asymptomatic in the initial stages, it can lead to important complications, such as heart failure, cryptogenic stroke, or, according to the most recent studies, cognitive disorders (like dementia).

What are the consequences and risks of atrial fibrillation?

The hemodynamic consequences and remodeling induced by atrial fibrillation translate, in clinical terms, into a reduction in the quality of life due to the appearance of important subjective disorders, in an increase in cardiovascular mortality, in a higher incidence of thromboembolic complications, and in the possible appearance of tachycardiomyopathy.

Quality of life is significantly reduced in subjects with atrial fibrillation compared to control subjects, with a lower score of 16% – 30% of all parameters commonly considered (general health status, physical functions, vitality, mental state, emotional functions, social role, physical pain).

If the heart rate is particularly high and the arrhythmia persists for weeks or months, the contractile force of the heart may progressively decrease and progress into heart failure.

Furthermore, in fibrillating atria (and in particular in their contractile appendages, called “auricles”) the blood tends to stagnate instead of being expelled from the normal contraction. The conditions are therefore created for the formation of clots (thrombi) which can migrate into the circulation as emboli.

Particularly dangerous are the emboli released from the left atrium because they can reach the cerebral circulation and cause serious damage, in particular thromboembolic stroke.

How is the diagnosis of atrial fibrillation made?

The diagnosis of atrial fibrillation itself is very simple, since an electrocardiographic trace, in particular the 12-lead ECG trace, is sufficient.

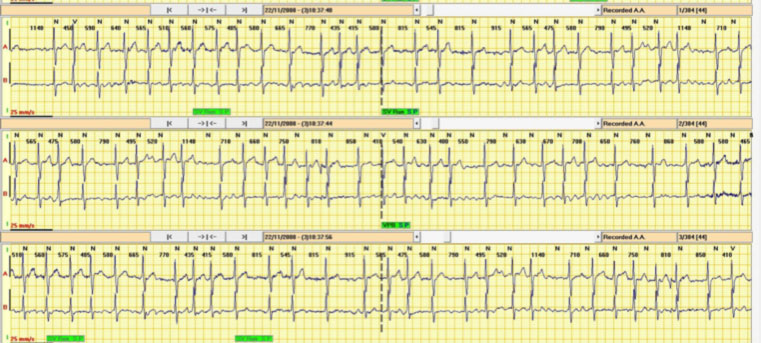

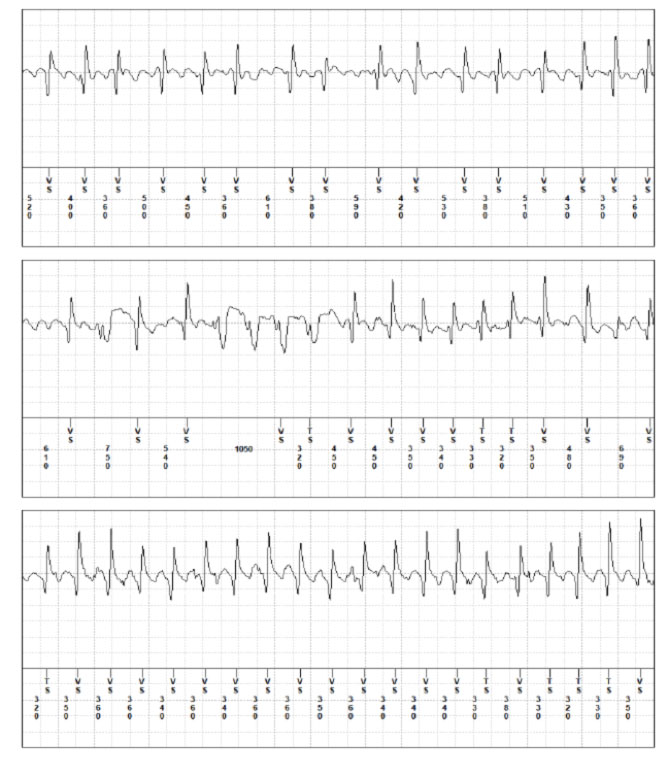

The problem is the difficulty in catching the arrhythmia when it is present (for the short duration or for the total lack of the reference symptoms). Even in follow-up, the main obstacle is the difficulty of detecting with certainty the episodes of atrial fibrillation.

For this we use prolonged electrocardiographic recording systems called dynamic ECG Holter (which can last from 24 hours to several days, generally up to a maximum of 30 days).

Then there are small long-lasting recording systems that are inserted subcutaneously through a small incision, called the “implantable loop recorder” (or ILR). These systems can last up to three years and can also be interrogated through remote monitoring, i.e. directly from the patient’s home, without requiring patient access to the hospital.

Recently, recording systems of short ECG traces are also available (generally about 30 sec, single channel) based on Smartphone technology, also through the iWatch system, which allow the patient to independently record a short ECG tracing, on which the system performs a first analysis and proposes a first diagnosis of the rhythm. The track can then be sent by email for verification by the Analysis Center: this service is called Cardiotelephone.

In addition to identifying atrial fibrillation with the electrocardiogram, a complete diagnostic framework is necessary to demonstrate or exclude cardiac or endocrine pathologies that cause or facilitate atrial fibrillation and require treatment.

What are the treatments for atrial fibrillation?

The treatment of a patient with atrial fibrillation requires knowledge of the aspects of arrhythmia presentation (paroxysmal, persistent, chronic), first event or recurrence, symptomatic or asymptomatic, and the basic clinical situation. Only later can decisions be made about whether or not an attempt should be made to restore the sinus rhythm, how to restore the sinus rhythm, and its subsequent maintenance.

Atrial fibrillation therapy is essentially based on these four aspects:

- Check for predisposing conditions (e.g. arterial hypertension, thyroid disorders, gastric disorders, etc)

- Prevention of arterial thromboembolism, through anticoagulant drugs

- Heart rhythm control, i.e. the attempt to restore sinus rhythm and prevent AF recurrence, particularly in the case of paroxysmal and persistent AF, essentially through antiarrhythmic drugs and transcatheter ablation

- Heart rate check (“rate control”), i.e. control of the frequency response, particularly in case of permanent atrial fibrillation, essentially through antiarrhythmic drugs, including beta-blocker drugs and digitalis.

At the first finding of atrial fibrillation, even if asymptomatic, the attempt to restore the sinus rhythm is indicated, providing it’s compatible with the patient’s age and the presence of co-pathologies. If the arrhythmia is of recent onset and in the absence of heart disease, the first therapeutic choice for the restoration of the sinus rhythm is antiarrhythmic drugs. In case of longer duration of the arrhythmia, or of heart disease, or of hemodynamic instability, the first therapeutic choice instead becomes the electrical cardioversion.

Regardless of the technique used for the restoration of the sinus rhythm, great attention must be paid to compliance with the protocols for the prevention of thromboembolic risk, in particular by evaluating the duration of the arrhythmia and any underlying heart disease.

After restoration of the sinus rhythm, in many cases no prophylaxis of recurrence is necessary (e.g. atrial fibrillation from correctable cause, or first episode of short duration and hemodynamically well tolerated). If, on the other hand, based on the clinical picture, prophylaxis is considered appropriate, the first therapeutic step is generally antiarrhythmic drugs, taken as needed or chronically.

In case of drug ineffectiveness or intolerance, or in case of recurrence, catheter ablation procedures may be considered as an alternative to chronic atrial fibrillation.

When is ablation of atrial fibrillation recommended?

In cases of paroxysmal or persistent AF, and in case of permanent atrial fibrillation in selected patients, today the Guidelines recommend carrying out radiofrequency transcatheter ablation (TCA-RF). This method is currently effective in about 70% of cases. In some cases, repetition of the ablation may be necessary to maintain the sinus rhythm.

Once atrial fibrillation is established, atrial tissue undergoes an “electrical” and “structural” remodeling, that is, changes in the electrophysiological and structural characteristics of the atrial myocardium towards fibrosis. These changes increase as a function of the duration of AF, decreasing the probability of restoring the sinus rhythm and maintaining it after cardioversion and after ablation. This concept is summarized by the phrase ”AF begets AF ”, that is “atrial fibrillation facilitates atrial fibrillation”. Therefore, today the Guidelines recommend carrying out ablation procedures in the early stage of atrial fibrillation, without postponing to a late stage in which atrial remodeling has already advanced.

After TCA-RF, it may be necessary to continue antiarrhythmic therapy and anticoagulant therapy. To guide the therapeutic management after ablation, the positioning of an implantable subcutaneous loop recorder, generally followed with remote monitoring, is useful.

When may pacemaker implantation be necessary for the management of atrial fibrillation?

In some cases, when the conduction beam towards the ventricles is damaged, and, therefore, the ventricular response of atrial fibrillation is particularly low, it may be necessary to resort to the implantation of a permanent pacemaker.

When it is not possible to control the ventricular response frequency of atrial fibrillation, which remains very high despite the drugs (beta-blockers and digital), it may be necessary to resort to ablation of the atrioventricular node associated with the implantation of a permanent pacemaker. In this case, a resynchronizer pacemaker (CRT-P) can often be chosen to maintain a physiological contraction in the two ventricles.