Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Indice dell'articolo

WHAT IS HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY?

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a heart muscle disease characterized by an increase in the thickness of the walls of the left ventricle (left ventricular hypertrophy, often at the level of the interventricular septum or cardiac apex), not secondary to arterial hypertension, to diseases of the heart valves or other systemic causes that can generate left ventricular hypertrophy. Patients have a sneaky onset with arrhythmias and sudden death may be the first clinical sign of the condition. The incidence is difficult to calculate because many patients have a syndromic picture, with anomalies affecting other organs and systems.

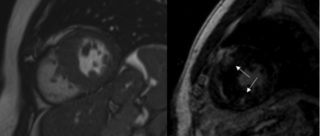

The development of hypertrophy usually occurs in adolescence or adulthood, generally later in females than in males, even up to the sixth or seventh decade of life, while only a minority of patients have hypertrophy already at birth or in childhood. The diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is made by echocardiography or magnetic resonance imaging, when a left ventricle wall thickness greater than 15 mm is observed in one or more segments of the left ventricle (more frequently in the interventricular septum, more rarely at the apical or diffusely on all walls).

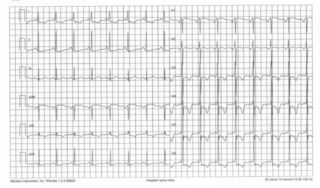

The disease can begin at any age, and a significant percentage of asymptomatic patients have sudden death as the only manifestation of the pathology. In symptomatic patients, it can present with dyspnea, palpitations, syncope and precordial pain. Nonspecific alterations of the ECG trace (with high QRS voltages and negative T waves) and arrhythmias (nodal re-entry tachycardia, atrial fibrillation and flutter, ventricular arrhythmias) can occur in many patients, especially those who have single copy mutations in the MYBPC3 gene.

WHAT IS THE PREVALENCE OF HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY?

HCM has been a clinical form known for centuries and is still a major cause of sudden death today. HCM is one of the most common forms of genetic heart disease. The prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the adult population, evaluated in different geographic areas and different populations (from the United States to Japan to Tanzania), is around 2:1000. Therefore, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is not considered a rare disease.

WHAT IS THE GENETIC BASIS OF HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY?

The causes of HCM are almost only genetic, and, among these, they can be syndromic or non-syndromic. Syndromic forms include Fabry disease, Noonan syndrome and Leopard syndrome. One of the syndromes most commonly associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is Noonan syndrome (on average 1/1700 live births). Among the non-syndromic forms, we can find amyloidosis and isolated forms of septal hypertrophy (among the most common in Europe and the USA).

HCM is caused by single or double copy mutations of the genes that encode cardiac muscle proteins. The genes most commonly implicated are MYBPC3, MYH7 and TNNT2, responsible for at least 60% of cases alone. A patient with HCM typically has only one copy of the causative gene mutated. It follows that the risk of recurrence is generally 50% for each pregnancy. The MYBPC3 gene has been found mutated in about ten of our patients suffering from Brugada syndrome, suggesting a gene substrate shared between the two diseases (unpublished data).

HCM transmission modality is usually “autosomal dominant”. This means that, in the majority of cases, the disease is transmitted from parent to child with a 50% probability. However, in some families, it is possible that the parent or the child does not have a clear clinical expression of the disease. This phenomenon is called “incomplete penetrance” and means that the pathology does not always occur in all patients with the genetic mutation.

WHAT ARE THE DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY?

Clinical diagnosis is based on the recognition of ventricular hypertrophy (in the presence or absence of a positive family history). It is defined as a left ventricular wall thickness of 15 mm or greater in adult patients. In the pediatric patient, a score is used that calculates the standard deviations by age. In these patients, the thickness of the septum is pathological if it is equal to or greater than 2 standard deviations for age. It is essential to exclude arterial hypertension and aortic valve stenosis in a patient of any age. In cases with family history, the criteria are less stringent, allowing a clinical diagnosis with a ventricular thickness equal to or greater than 13 mm. It is important to know that some valve abnormalities (e.g. mitral prolapse or myocardial cleft) can support a suspicion of HCM, rather than rule it out.

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS OF HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY?

Initially, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is often asymptomatic, or the symptoms may be misinterpreted by the patient. In these cases, the diagnosis is made during checks performed for other reasons, such as during a sports medical examination. The most common symptoms, when present, are palpitations, dyspnea (“shortness of breath”) during exertion, chest pain at rest or from exertion, or syncope (“sudden fainting”), often during exertion.

In most cases, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is a relatively benign heart disease, with stability of symptoms and hypertrophy itself in the decades following diagnosis. However, over the years, approximately 20% of patients may experience worsening of symptoms and complications, such as arrhythmias, both atrial (especially atrial fibrillation) and ventricular, as well as ventricular extrasystoles, and unsustained or sustained ventricular tachycardias, which can cause syncope (loss of consciousness), or ventricular fibrillation (which causes cardiac arrest and sudden death).

WHAT IS THE DIAGNOSTIC PROCESS OF HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY?

The HCM diagnostic process includes, in addition to the cardiological examination, the electrocardiogram and the transthoracic echocardiogram, the dynamic Holter ECG, stress test or cardiorespiratory test, and cardiac magnetic resonance with contrast medium.

These investigations enable the evaluation of the severity of heart disease and the potential risk of complications. To these data are added the information provided by the genetic examination (carried out with the patient’s consent after genetic counseling).

Once the diagnosis has been made, the first degree relatives of the patient (parents, siblings, children) are invited to perform the basic cardiological tests (visit, electrocardiogram, and echocardiogram) in order to evaluate whether some of them also show signs of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. When the responsible genetic mutation has been identified in the patient, it is also sought in first-degree family members. The contribution of genetic testing is important in family screening because it enables the identification of family members carrying the genetic mutation responsible for the disease before symptoms appear.

WHAT ARE THE HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY THERAPIES?

At the moment, there is no cure that heals hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, however there are therapies to improve the symptoms and prevent any complications. The need and choice of treatment is personalized, different for each patient. The drugs most used in patients are beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers. Anticoagulant medications may be needed for atrial fibrillation. In case of arrhythmias, class 1a and 1c antiarrhythmic drugs can be used, more rarely amiodarone. In case of heart failure, diuretics and ACE inhibitors can be used.

WHEN IS THE DEFIBRILLATOR IMPLANTATION NECESSARY IN HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY?

Patients with HCM at high risk of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death are candidates for the implantation of an automatic defibrillator (Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator or ICD). Both survivors of cardiac arrest (secondary prevention) and patients in primary prevention considered to be at high risk because of the presence of repetitive ventricular arrhythmias or with a family history of sudden death due to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy are candidates for the ICD implantation. The ICD is able to identify potentially lethal arrhythmias and give an electric shock (or to do an anti-tachycardia stimulation) to stop these arrhythmias and restore normal heart rhythm. Patients should still be informed of possible complications associated with an ICD, which include inappropriate electrical discharges during high but normal heart rates (currently, these inappropriate interventions occur in nearly 25% of patients), often due to problems with the catheters (usually, catheter rupture, relatively frequent in these patients). The period of exposure to the risk of sudden death is typically very long in HCM (theoretically 20-50 years in some patients), and therefore the ICD is likely to intervene for the first time only after years (5-10 years) since the implant.

WHEN IS SURGERY NECESSARY IN HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY?

About 30% of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy already have an obstruction in the left ventricular outflow tract at rest, which can be assessed and measured with transthoracic ultrasound. The hypertrophy of the interventricular septum, combined with the displacement of the mitral valve apparatus, reduces the size of the passage area between the left ventricle and aorta (“outflow tract”), so as to require a higher pressure (“gradient”) to expel blood from the ventricle to the aorta.

The obstruction may be absent at rest but present during exercise in an additional 30% of patients, and this phenomenon can be assessed with the ColorDoppler echocardiographic examination performed during exercise tests.

If the obstruction is severe and causes important symptoms (dizziness, fainting, chest pain), its reduction may be indicated, which is usually done with cardiac surgery (myectomy), to be performed in centers with consolidated experience.