Atrial tachycardias

Indice dell'articolo

What is atrial tachycardia?

Atrial tachycardia (AT) is a heart rhythm disorder that originates in the atria, defined as a supraventricular tachycardia that does not require the participation of the atrioventricular junction, accessory pathways, or ventricular tissue for its onset or maintenance. Atrial tachycardia is an infrequent condition and accounts for 5-15% of all supraventricular tachycardias, and it is more frequent in patients with congenital heart disease or in post-surgical patients.

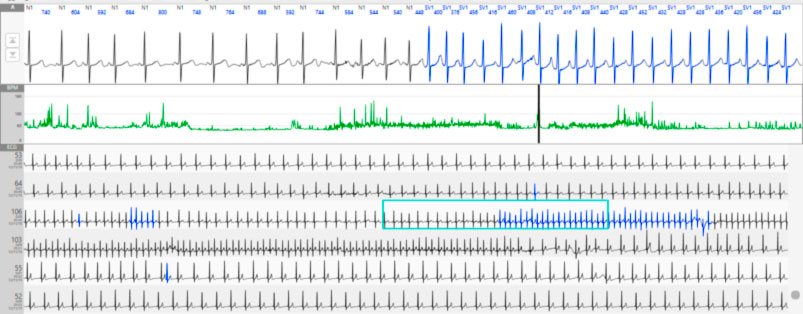

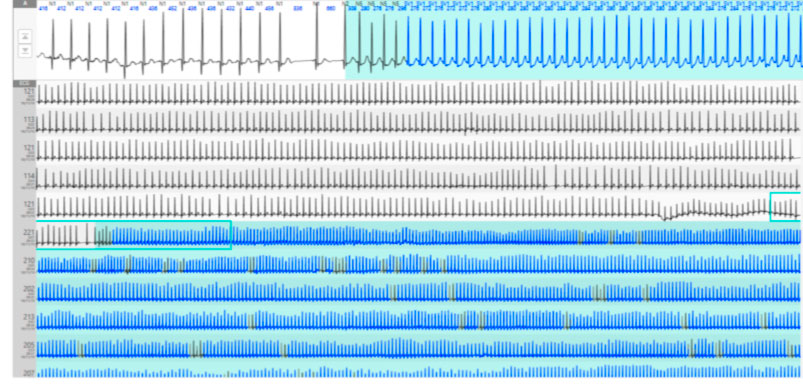

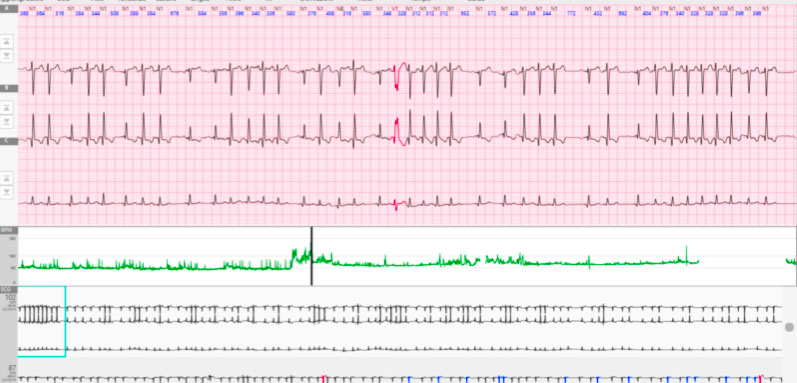

In the case of atrial tachycardia, the ECG typically shows a tachycardia at a narrow QRS (unless there is a conduction aberrance or a bundle branch block). The heart rate in tachycardia is typically between 150 and 250 beats per minute. The atrial rhythm is usually regular. The ventricular rhythm also is usually regular, however, it may become irregular due to a variable blockage at the level of the A-V node. In this case, it is not difficult to observe conduction patterns such as 2:1 or 4:1, sometimes also in combination. The morphology of the P wave observed on the surface ECG could give indications regarding the site of onset and the mechanism of atrial tachycardia. In the case of a focal atrial tachycardia, the morphology of the P wave, together with the P axis, are very suggestive of its origin (which is not equally true for macro-re-entry atrial tachycardias).

What are the symptoms and prognosis of atrial tachycardias?

Patients may experience palpitations, chest pain, fatigue, shortness of breath, or reduced exercise tolerance. Some patients, even children, with incessant atrial tachycardia may develop tachycardiomyopathy and consequently congestive heart failure.

In structurally healthy hearts, this arrhythmia usually has a good prognosis. When tachycardia is persistent or incessant, it can lead to myopathy, and consequently to ventricular dilation and a reduction in the ejection fraction. Patients with underlying heart disease or with pneumological concerns generally can tolerate tachycardia less.

What are the classification criteria and mechanisms of atrial tachycardia?

Atrial tachycardias can be classified based on endocardial activation data, pathophysiological mechanisms, or anatomy.

Based on endocardial activation, atrial tachycardias can be divided into two groups: focal atrial tachycardias (originating from a well-localized area) and atrial re-entry tachycardias (usually a macro-center). Most commonly, a macro-center needs a substrate (such as a scar or anatomical anomaly) that can be congenital or caused by surgery. Differential diagnosis between atrial tachycardia and flutter is often not easy. The pathophysiology is similar (re-entry) and the definition is typically based on the length of the atrial cycle (cut-off 250 msec > atrial flutter) or on the presence of an isoelectric line between the P waves (characteristic of atrial tachycardias).

Based on the pathophysiological mechanism, atrial tachycardias can be classified into: tachycardia due to increased automatism, triggered activity, and re-entry.

The anatomical classification instead takes into account the location of the arrhythmogenic focus. Ectopic atrial tachycardias can originate from both the left atrium and the right atrium. Some atrial tachycardias can originate from unusual sites such as the superior vena cava, the coronary sinus, the pulmonary veins and the Marshall ligament due to the penetration of myocardial islets inside these structures.

Many atrial structures can represent a substrate for arrhythmia. The orifices of the vena cava, the pulmonary veins, the coronary sinus, the atrial septum, the tricuspid, and the mitral annulus are potential anatomical barriers that can favor the re-entry circuits. The anisotropy of the atria due to the orientation of the muscle fibers could create a slow conduction zone. The terminal crest and pulmonary veins are sites where increased automatism or triggered activity is commonly found. In addition, degeneration and fibrosis of the atrial tissue could create a substrate for arrhythmias.

-

Atrial tachycardias due to increased automatism.

Automatic atrial tachycardia is found both in patients with a structurally healthy heart and in patients with underlying heart disease. Tachycardia is typically difficult to induce during the electrophysiological study, and induction protocols are not reproducible. It often occurs spontaneously or after isoproterenol infusion. Carotid sinus massage and adenosine do not end tachycardia but have the effect of producing a transient A-V block.

The criteria that have been proposed for the diagnosis of automatic atrial tachycardia are the following: 1) Spontaneous onset without correlation with critical frequencies or coupling intervals; 2) Constant endocardial activation pattern from the first beat; 3) Inability to induce or end tachycardia with atrial or ventricular stimulation; 4) Demonstration of the warm-up phase at the beginning of tachycardia; 5) Ability to reset tachycardia with earlier atrial extrasystoles; 6) Suppression of tachycardia with rapid atrial pacing manoeuvres; 7) P-R is related to the frequency of tachycardia; 8) P waves differ from sinus (for differential diagnosis with inappropriate sinus tachycardia).

-

Atrial tachycardias from triggered activity

Triggered atrial tachycardias are due to late post-depolarizations, which are made up of low voltage oscillations at the end of the action potential. These oscillations are triggered by the previous action potential and are favored by the flow of calcium ions into the myocytes. If these oscillations are of sufficient amplitude to reach a certain threshold of action potential, a new depolarization is triggered, and therefore a new action potential. If the phenomenon is single, it will give rise to an atrial extrasystole. If it is recurrent and spontaneous depolarization continues, it will result in sustained atrial tachycardia. These tachycardias can also be induced with rapid atrial pacing. Most commonly, atrial tachycardia due to triggered activity occurs in patients with digitalis intoxication or with conditions associated with an excess of catecholamines. It can respond to measures such as vagal manoeuvres or medications such as adenosine, verapamil or beta-blockers by increasing the refractory period of the myocardium. Occasionally atrial tachycardia can originate from multiple atrial sites producing a multifocal or multifaceted tachycardia. This can be recognized by the different morphologies of the P wave and by the irregularity of the atrial rhythm.

The criteria used for the diagnosis of atrial tachycardia from triggered activity are as follows: 1) it can be induced through programmed atrial stimulation and atrial pacing and is independent of the atrial conduction delay and the atrioventricular conduction delay; 2) Atrial pacing, cycle length and the coupling interval of atrial extrasystoles are directly related to the interval of onset of atrial tachycardia and to the initial length of the tachycardia cycle; 3) P-R is related to the frequency of tachycardia; 4) The degree of blockage of the tachycardia does not affect the cycle of the same; 5) acceleration of tachycardia during overdrive is also a typical electrophysiological finding.

Tachycardias originating from the pulmonary veins usually originate from the hosts of the same or from atrial fibers placed deeper. These tachycardias are very rapid (more than 200 bpm), and although they frequently trigger atrial fibrillation episodes, they can sometimes present as stand-alone arrhythmias. In this case, they typically involve a single pulmonary vein, rather than multiple pulmonary veins, as occurs in atrial fibrillation.

-

Return atrial tachycardias

Intra-atrial re-entry tachycardias can be due to both macro-reenteries and micro-indentations. The return is an expression of an anomaly in the propagation of the impulse. These can be caused by anatomical or functional anomalies, or by a combination of these, which cause an inhomogeneity of the electrophysiological substrate essential to support the re-entry.

Because a re-entry circuit is possible, three conditions are indispensable: 1) at least two pathways of propagation of the impulse must be present, whether anatomical or functional, which must join proximally and distally to form a closed circuit; 2) In one of these ways there must be a one-way block; 3) the conduction along the unblocked way must be slowed down allowing the blocked way to restore its excitability. From this it follows that the conduction time along the slow path must be greater than the refractory period of the blocked path. If, and only if, conduction delay and refractoriness in both ways are appropriate, the wavefront can continue to propagate indefinitely along the circuit supporting the tachycardia. Macroreentry is the typical mechanism of atrial flutter and of post-incisional (post-surgical) atrial tachycardias.

The most common form of macroreentry atrial tachycardia, with the advent of circumferential ablation of the pulmonary veins, is left atrial tachycardia, depending on the gaps that can occur in the lesions. In fact, these cause a slowing down of conduction, creating the ideal substrate for re-entry. They can be self-limiting but could also occur in a persistent form; in this case a new mapping and a new ablative procedure should be considered.

Micro-re-entry, on the other hand, generally involves a small area, as in the case of sinus re-entry tachycardia. Typically, atrial re-entry tachycardia is characterized by sudden onset and cessation, and is therefore paroxysmal. Carotid sinus massage and adenosine are ineffective in ending tachycardia, even if they produce a transient A-V block. During the electrophysiological study, it can be induced and terminated through programmed atrial stimulation. As with all other rebound arrhythmias, atrial tachycardia can also be terminated by external electrical cardioversion.

Often re-entry AT enters differential diagnosis with other supraventricular arrhythmias, such as AVRT (atrio-ventricular re-entry tachycardias) and NRT (nodal re-entry tachycardias) .The following information may be useful for their differentiation: 1) Spontaneous or induced A-V blocking does not affect tachycardia and this eliminates the hypothesis of an A-V re-entry, 2) If the bundle branch block does not affect the tachycardia cycle or the A-V conduction intervals, this leads to a AVRT, 3) If during the mapping to identify the arrhythmia origin site, it is placed outside the A-V ring or the A-V node, the hypothesis of a AVRT or NRT can be excluded; 4) If with programmed ventricular stimulation there is atrial preexcitation despite the refractoriness of the His bundle, this poses in favor of an accessory route; 5) If ventricular stimulation is effective in ending the arrhythmia, retrograde conduction of the premature beat should be present. If, on the other hand, ventricular extrastimulus is not conducted to the atrium and causes the arrhythmia to cease, then the hypothesis of atrial tachycardia can be excluded; 6) Spontaneous interruption of tachycardia in a patient who has not demonstrated AV block during tachycardia is associated with intact A-V conduction. In this case, if the tachycardia spontaneously stops without the need for an atrial extrastimulus, the diagnosis of AT is unlikely.

What are the ECG characteristics of atrial tachycardia?

The ECG is an important tool to identify, locate and differentiate atrial tachycardias. The ECG characteristics of atrial tachycardia include: 1) Alterations in the morphology and axis of the P wave; 2) alterations in the PR interval; 3) Changes in the P-P interval.

Typically ectopic atrial tachycardia can be differentiated from other atrial arrhythmias by macro-reentry based on the presence or absence of the isoelectric line between two P waves. The morphology of the P wave in the aVL and V1 leads is very useful for the localization of the arrhythmic focus (right or left). A positive or biphasic P wave in the aVL derivation predicts a right focus with 88% sensitivity and 79% specificity. A positive P wave in V1 predicts a left atrial focus with a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 88%. In many cases, the P-R interval is shorter than the R-P interval. However, in the presence of an A-V conduction delay, the PR interval may be longer than the RP; in these cases, the P wave seems to follow the QRS complex or fall within the same, simulating a NRT. Since the A-V node is not part of a return circuit, it is not uncommon to find a conduction block (2:1 or 4:1) without, however, witnessing the interruption of tachycardia. An atrial tachycardia with conduction block is highly suggestive of digitalis intoxication, especially if associated with alterations of repolarization.

Diagnostic criteria for multifocal atrial tachycardia include: 1) an irregular atrial rate greater than 100 bpm; 2) at least 3 different P wave morphologies without, however, evidence of a dominant pacemaker; 3) irregular PP interval; 4) presence of the isoelectric line between the P waves. This form of tachycardia is often associated with lung diseases, such as COPD in the exacerbation phase, or alterations of electrolytes. Occasionally, if the arrhythmia mechanism is increased automatism or triggered activity, the stress test could be useful to facilitate the induction of the arrhythmia.

What are the clinical pictures and the differential diagnosis of atrial tachycardias?

Atrial tachycardia can affect both individuals with a structurally healthy heart and patients with underlying heart conditions. Rebound atrial tachycardia tends to affect patients with structural heart disease, including valvular heart disease, congenital heart disease and post-surgical heart disease. When atrial tachycardia affects patients with congenital heart disease who have undergone corrective or palliative surgical procedures, it takes on a more frequent form and has life-threatening consequences.

The atrial tachycardia that occurs during exercise, during acute diseases involving the release of catecholamines, or after ingestion of alcohol, dehydration, metabolic alterations, use of sympathetic mimetic substances (caffeine, theophylline, cocaine, amphetamine) is associated with increased automatism or triggered activity. Digitalis intoxication is an important cause of atrial tachycardia from triggered activity.

Multifocal atrial tachycardia is a very particular tachycardia in which multiple arrhythmic foci are found. It is often found in patients with COPD exacerbations, pulmonary thromboembolism, congestive heart failure, or use of inotropic (digitalis) drugs. Unusual forms of atrial tachycardia can be observed in patients with infiltrative processes affecting the pericardium and the atrial wall (lymphoma).

Differential diagnosis of atrial tachycardia is made with the following: sinus tachycardia, atrial flutter, atrial fibrillation, AVRT, NRT. The ECG of a supraventricular tachycardia usually shows narrow QRS (unless there is an aberrance conduction). The evaluation of the P wave and its relationship with the QRS complexes makes two situations possible:

AT with short PR and long PR; in this case the differential diagnosis is made with AVRT, NRT, AT with first degree AV block, junctional tachycardia, and atrial tachycardia originating from the coronary sinus ostium. Diagnosis often requires additional manoeuvres, such as vagal stimulation, (MSC, Valsalva etc.) or adenosine.

AT with long PR interval and short PR; the differential diagnosis includes atypical NRTs, such as fast-slow, AVRT, reciprocal junctional tachycardia due to a slow accessory pathway with slow retrograde conduction, sinus tachycardia and sinus re-entry tachycardia. The diagnosis also includes the evaluation of conditions such as anaemia, thyroid dysfunction, kidney failure, electrolyte imbalances, lung disease, drug therapy, and previous cardiac surgery.

For multifocal atrial tachycardia, differential diagnosis includes atrial fibrillation, as both can present with an irregular pulse.

Another chapter is that of iatrogenic atrial tachycardias. Various typical sites have been identified for these tachycardias. These locations include the mitral isthmus (between the inferior pulmonary vein and the mitral annulus, the roof of the left atrium and the remaining pulmonary veins. The most frequent causes of these tachycardias are the gaps that can be created in the lesions that create the ideal substrate for re-entry circuits. For those who have undergone surgical procedures, atrial macro-reentry tachycardias are more frequent.

What is the therapy for atrial tachycardias?

Vagal manoeuvres are the first choice treatment in hemodynamically stable patients. The Valsalva manoeuvre, the carotid sinus massage, and acupressure of the eyeballs, causing a slowing of the conduction are potentially effective in interrupting the arrhythmia: these interventions are generally less effective than in NRT or AVRT.

When vagal manoeuvres are ineffective, pharmacological conversion may be attempted, with class 1c or class 3 antiarrhythmic drugs. On the other hand, adenosine in bolus i.v. is basically ineffective in atrial tachycardia and sinus re-entry tachycardia. Beta-blocker drugs, such as metoprolol or esmolol, can also be tried and are effective, in particular, in tachycardia due to increased automatism.

The external electrical cardioversion is instead used in case of compromise of the hemodynamic state, when the patient is hypotensive, is in pulmonary edema, or experiences chest pain. The choice of long-term therapy for patients with atrial tachycardia depends on the symptoms, the frequency of the episodes, and the underlying heart conditions.

RF ablation should be considered in all patients refractory to medical therapy or in those in whom antiarrhythmics are contraindicated.